With his arrangement of Schlummert ein from Johann Sebastian Bach’s cantata Ich habe genuch, Simon Steen-Andersens literally extinguishes the light and movingly depicts Bach’s ‘lullaby of eternal sleep’. In the world-famous Light Music by Thierry De Mey (known from Musique de table), a soloist ‘paints’ light and sound, as it were, via his hands connected to wifi sensors. Serge Verstockt switches off all visual stimuli to clear the path for primal instinctive listening. Through the lighting and blowing out of matches, a surprising and tactile sound sculpture emerges. Mátyás Wettl gives a totally new radical but playful interpretation of the Nocturne‘s compositional form. No piano but 16 light switches guarantee a virtuoso world wind of light and sound.

PROGRAM

- Serge Verstockt: Part I from DRIE (2007/2022)

- Alexander Schubert: Sensate Focus (2014)

- Thierry De Mey: Light Music (2004/2021)

- Simon Steen-Andersen: Schlummert ein (2013)

- Mátyás Wettl: Nocturne (2017)

This program is also possible in combination with other works by Natacha Diels (An economy of means), Yoko Ono (Lighting Piece) or Salvatore Sciarrino (L’orrizonte luminoso die Aton)

Program notes by Jannis Van de Sande for DE SINGEL

Adventurous programmes that stimulate multiple senses: it has long been Nadar’s trademark. In Light Music, the ensemble explores the synergy between – you guessed it – sound and light. They do so using a series of (relatively ) recent compositions, in which light becomes part of the music in a structural way. The very first performance of the Light Music programme coincided, not coincidentally, with the Catholic holiday Candlemas, which takes place on 2 February, or 39 days after Christmas. So although we have already passed Candle Mass 2025, the programme promises to take us into mystical spheres more than once.

Mystical atmospheres are already present in Simon Steen-Andersen’s Schlummert ein.

That the paths of the Danish composer and Nadar constantly cross is certainly no coincidence: his inventive and playful approach is tailor-made for the ensemble. Schlummert ein is a fine example of this. It is an arrangement of Bach’s bass aria of the same name, from the religious cantata Ich habe genug, composed incidentally for Candlemas. Juister still, Steen-Andersen sets to work with an old recording by Hans Hotter, which is imitated live by three musicians. The keyboard follows the organ part, the cello imitates the strings, and the singing voice from the original is doubled by the trombone. The real ingenuity, however, lies in the fact that the recording plays slower and slower. Through microtonal intervals, the musicians try to keep the tempo of the slabbing record, and uncanny friction ensues. Meanwhile, the light also gradually dims, completing the parallel with the protagonist from Bach’s aria. Indeed, that one closes his eyes forever, heading for a world beyond ours. The light is off, the tone set.

Schlummert ein, ihr matten Augen,

Fallet sanft und selig zu!

Welt, ich bleibe nicht mehr hier,

Hab ich doch kein Teil and dir,

Das der Seele könnte taugen.

Hier muss ich das Elend bauen,

Aber dort, dort werd ich schauen

Süssen Frieden, stille Ruh.

For the performers, while Schlummert ein is a particularly challenging score, the concept itself is sparklingly simple at its base. Yet Yoko Ono effortlessly outshines Steen- Andersen in terms of uncomplicatedness. The ‘score’ for her Lighting piece, a typical example of her LIGHT MUSIC conceptual compositional practice, contains only a simple instruction: ignite a match and watch until it goes out. Elevating such a mundane, almost banal act to art is completely in line with the philosophy of the Fluxus movement she was part of.

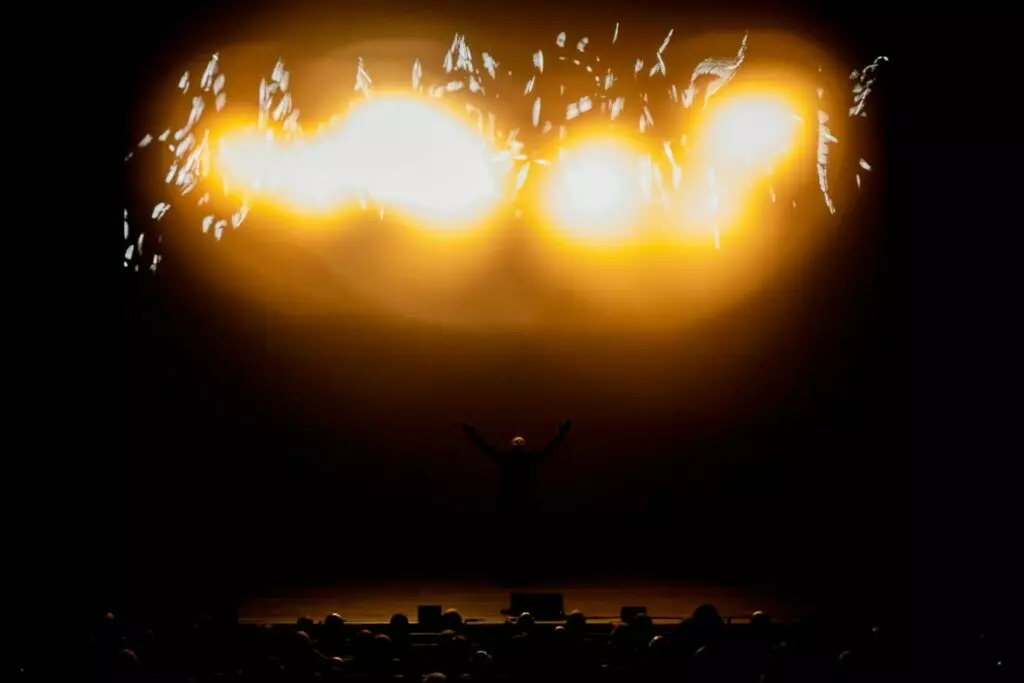

One of the centrepieces on the programme, which after all takes its title from it, is Thierry De Mey‘s Light Music. De Mey is a composer and filmmaker and enjoys international recognition for the music he has written for dance companies such as Rosas and Ultima Vez. Light Music spectacularly straddles those various spheres of interest, which since a passage to the Paris IRCAM in the early 1990s can also be counted as (music) technology. The work was written for solo conductor and live electronics. Using sensors, the hand movements of the conductor, facing the audience on stage, are converted into sounds, which in turn are manipulated live in space. The hand movements are not only illuminated in the otherwise dark space, but also projected behind the conductor. In the process, however, delays are built in, creating a complex play of light, movement and, of course, sound unfolds. De Mey wrote Light Music in 2004. The fact that the good twenty-year-old work does not feel dated at all today is probably partly due to the various revisions it has undergone since its creation and in the light of rapidly evolving technology. In the most recent and sweeping update, Thomas Moore, trombonist and conductor at Nadar, played a key role. In collaboration with Centre Henri Pousseur and De Mey himself, the outdated performance software was completely overhauled. But the content of Light Music, which until then had been performed exclusively by percussionist Jean Geoffroy, was also tinkered with. If the original score was indeed essentially written entirely to the beat of a percussionist, Moore and De Mey wanted to bring the composition closer to the conductor’s practice and the associated repertoire of movements. The fact that the performer on stage in this revised version conducts rather than generates the sound adds an interesting new dimension to an already highly layered composition.

Like Steen-Andersen, Alexander Schubert is a fixture in the Nadar universe, and let that too be no coincidence. His thoroughly multidisciplinary view on the music business rhymes unison with the ensemble’s philosophy. Schubert is undoubtedly one of the leading exponents of a generation of composers who have made a name for themselves over the past two decades with cross-disciplinary, multimedia and often theatrical work, eagerly referencing popular and everyday culture. Schubert’s Sensate Focus from 2014 definitely exemplifies this trend.

An ingenious lighting design reveals only fragments from a whole shrouded in darkness, which we never get to see as such. Flashes of light direct and accentuate the listening experience, but just as well they put us on the wrong foot at times. A stroboscopic finale clearly betrays Schubert’s fascination with rave culture, to which he also likes to refer in other compositions.

Nadar closes appropriately with a Nocturne, albeit one for a rather unusual instrumentation. In fact, Mátyás Wettl composed the work for 16 light switches. Anyone who has ever marvelled at the rhythmic light play of which a single switch is capable can already imagine the polyphonic potential of a multiple of these. Although the patterns themselves are accurately noted in the score, Wettl actually gives no instructions on the lights to be used themselves or their arrangement, and this creates possibilities. Nadar invited the students of the In Situ course at the Antwerp Conservatory to create their own lighting design for this performance. Here on the stage, the premiere features the invention by Gabriel Siams: a construction with 8 inverted lampposts, a particularly unusual instrument even for Nadar.