Program

- Abbas Kiarostami: The Chorus – short movie (1982)

- Golnaz Shariatzadeh: Bluer Womb for ensemble, electronics and animation (WP)

- Alexander Khubeev: Don’t leave the room and Silentium! for solo performer, ensemble, electronics and live video (WP)

Production: Gaudeamus Utrecht, DE SINGEL, Musica Strasbourg, Muziekcentrum De Bijloke Ghent, Nadar Ensemble, Ultima Oslo Contemporary Music Festival

Bluer Womb and Silentium! are commissioned by Nadar Ensemble with the support of the Ernst von Siemens Music Foundation // Silentium! is commissioned by Ultima Oslo Contemporary Music Festival and Gaudeamus as part of the ULYSSES Platform, co-funded by the European Union

Program Notes

In 1969, the Russian poet Joseph Brodsky (1940–1996) wrote a poem that would become known by its opening line: Don’t leave the room. In six quatrains, he urges the reader to stay indoors. After all, why go outside when you have four walls, a bed, and enough cigarettes?

Over the years, much has been speculated about the meaning behind Brodsky’s words. Is it an ode to voluntary seclusion, a call for self-censorship, an ironic warning to steer clear of the KGB? Or perhaps a quiet, coded plea to break the silence and resist?

In this interdisciplinary concert, these interpretations converge — and are refracted through new, contemporary lenses. In Don’t Leave the Room and Silentium!, Alexander Khubeev explores the psychological and political mechanics of censorship and self-censorship, using sign language as a deafeningly silent metaphor. In Bluer Womb, Golnaz Shariatzadeh creates an imaginary space where memory and mourning for the 2022 Iranian uprising intertwine with hope — a deeply personal yet universal search for refuge in times of political repression.

Musical Doublethink

It was early 2020 when composer Alexander Khubeev received a message from the Aksenov Foundation: would he like to write a new work for their Russian Music 2.0 project? He was given carte blanche — complete artistic freedom.

As it happened, Khubeev (b. 1986) already had something in mind. For a while, he’d been toying with the idea of creating a piece centered around sign language. “I’ve always been fascinated by the relationship between music and gesture,” he says over a video call in early June. “And the more I immersed myself in sign language, the more I realized how semantically rich and nuanced it is — that it could perform a poem just as vocal music might, only with the hands instead of the voice.”

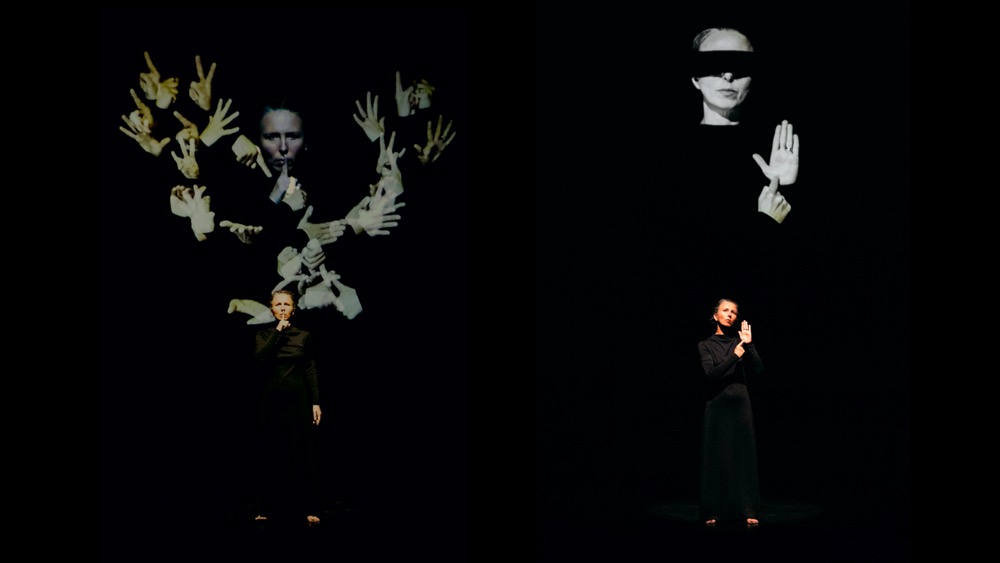

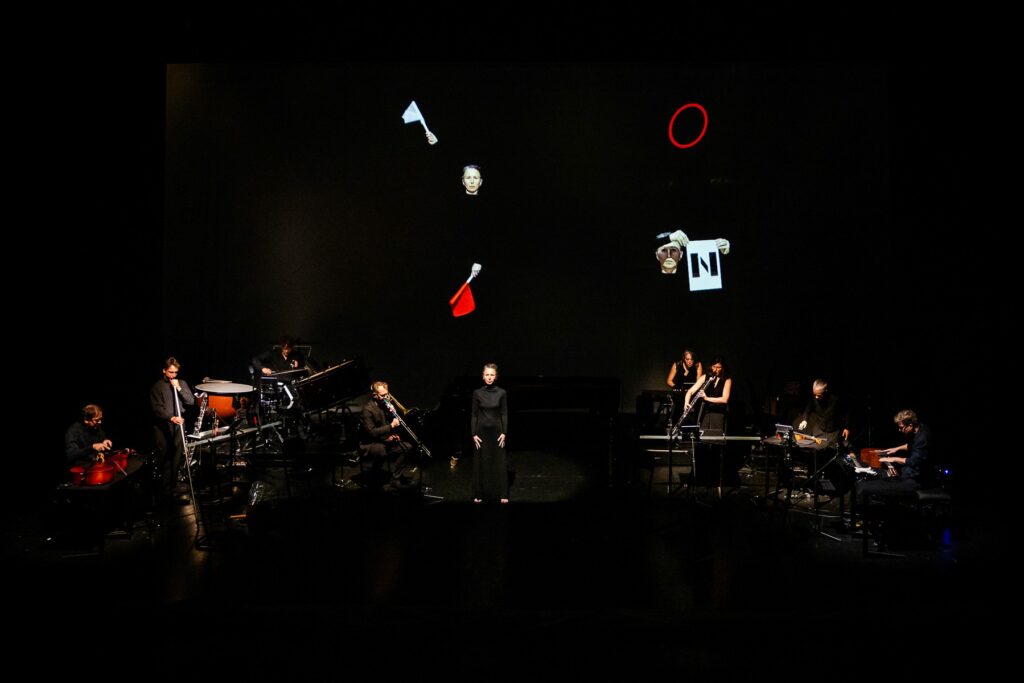

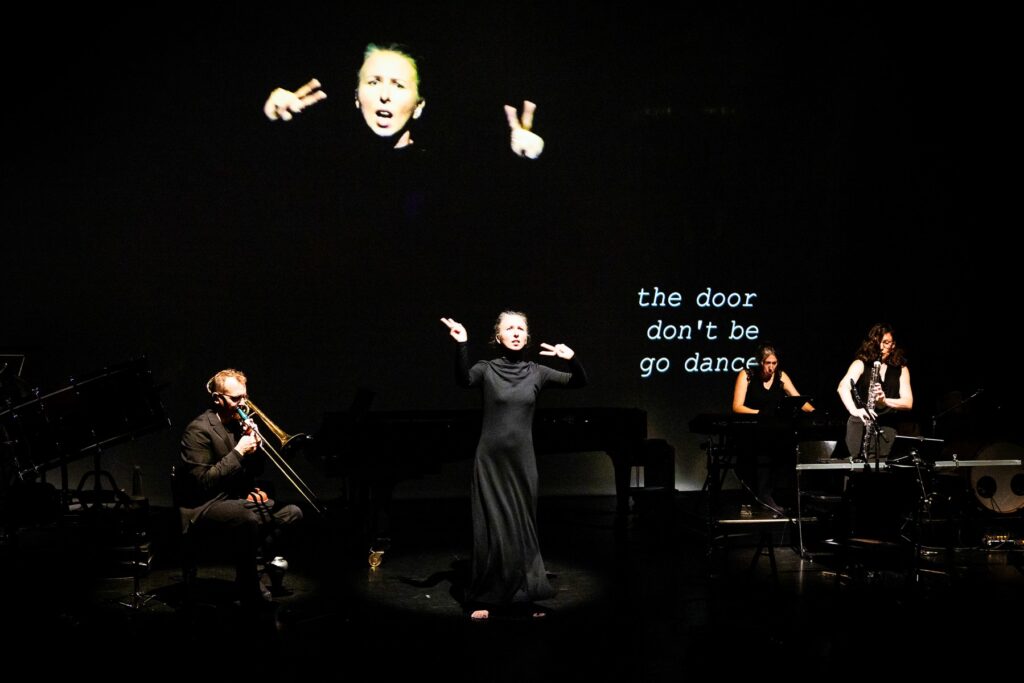

That idea took shape in Don’t Leave the Room, where a solo performer — both live and virtual — translates Brodsky’s poem into multiple systems of sign: Russian Sign Language, military hand signals, and the semaphore alphabet. Throughout, new forms of interaction emerge between the soloist’s gestures and the seven-piece ensemble, which draws on a striking palette of extended techniques. Wind players sound metal tubes; string players rub their instruments with ribbed doorstops, coaxing out brittle, unfamiliar textures.

Yet as Khubeev was writing, the piece was overtaken by reality. The COVID-19 pandemic hit. The whole world suddenly found itself locked indoors. Still, for Khubeev, Don’t Leave the Room speaks to something deeper. “At its core, this work is about censorship,” he explains. “Not just top-down suppression under an authoritarian regime, but the self-censorship we impose on ourselves — out of fear, survival, or habit. That internal silence, and the isolation it creates, is what this piece is really about.”

Sign language, in this context, is no mere concept — it becomes a metaphor. A way of capturing the deafening silence of someone with something urgent to say, but no means — or no courage — to say it aloud. The parallel with Russia’s political climate — “already palpable in 2020,” as Khubeev notes — is hard to ignore.

In the final bars of Don’t Leave the Room, a remarkable image unfolds: the projected figure of the soloist suddenly splits and multiplies. In a moment, she is locked in frantic conversation with three identical versions of herself. Asked about the scene, Khubeev says: “That image captures the psychological consequences of censorship. What can’t be said aloud begins to split off and live its own life inside your mind. You speak one thing while thinking another.”

That very notion — what Khubeev, borrowing from George Orwell’s 1984, calls doublethink — became the seed for his next composition, written for the Nadar Ensemble. Silentium, named after Fyodor Tyutchev’s 1830 poem, serves as a kind of companion piece to Don’t Leave the Room. In it, Tyutchev urges the reader toward inner silence, suggesting that true thoughts and feelings are best left unspoken.

At first glance, the parallels between Brodsky and Tyutchev seem clear. But for Khubeev, there’s a crucial difference: “Brodsky’s poem is full of irony. He tells you to stay in the room, but really he’s inciting you to resist. Tyutchev is different. He truly means it. His silence is a survival strategy — a response to a reality where speaking is not an option.” Doublethink, avant la lettre.

That duality carries into the musical structure of Silentium, which Khubeev describes as more polyphonic than its predecessor. Where the soloist and her projections once moved in tight synchrony, they now drift apart, becoming counterpoints — even contradictions — of one another. The sound world is also broader, with the addition of electronics, self-built instruments, and even more unconventional playing techniques.

One of Khubeev’s favorites? A three-meter-long steel wire strung with a soda bottle as resonator — to be plucked, bowed, or simply left humming in the air.

Barrage of Clusters

Did Joseph Brodsky and Galina Ustvolskaya (1919–2006) ever meet? In theory, they could have — both lived in Saint Petersburg (then called Leningrad) until Brodsky fled to America in 1972, following relentless persecution by the Soviet authorities.

In practice, however, things were less straightforward. As conductor Reinbert de Leeuw discovered while filming the documentary series Toonmeesters, Ustvolskaya rarely set foot outside her cramped apartment. There, in self-imposed isolation, she worked on a body of music as uncompromising as it is incomparable. For the desk drawer, as the saying goes — her music (keywords: unyielding, impenetrable) stood no chance of passing Soviet censorship. Take her Sixth Piano Sonata from 1988, in which the pianist hammers out a barrage of fortississimo clusters using the flat of the hand and forearm. Near the end, as if from nowhere, a handful of mysterious, whispering chords emerges — a moment of stillness in an otherwise relentless sound world.

Sanctuaries of the imagination

Iranian composer and visual artist Golnaz Shariatzadeh (b. 1996) was seventeen when she left for the United States to pursue her dream of becoming a concert violinist. Things turned out differently. While studying at Juilliard, she discovered her true passion lay in composing — and so it began. She is currently pursuing a PhD in composition at Harvard University, studying under Chaya Czernowin.

Call it a case of fate asserting itself. Even as a child, Shariatzadeh would invent stories and translate them into drawings: fantasy worlds, mysterious cities, secret chambers. It was, in her own words, a way to survive under the yoke of a totalitarian regime. “Growing up in Iran meant there was never a boundary between the personal and the political. To escape, I created my own spaces — places where I could retreat.”

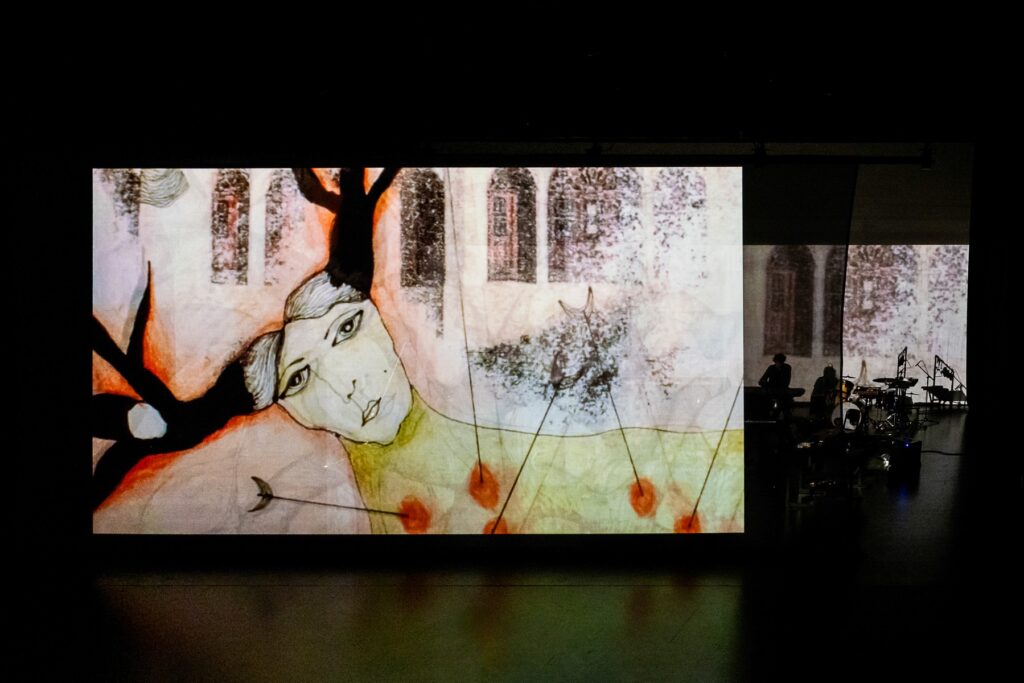

The idea of imagination as sanctuary, as refuge, still runs like a red thread through Shariatzadeh’s work. In it, she weaves an intimate yet charged sound world — balanced on the edge between acoustic instruments and electronics — with poetic, haunting stop-motion animations.

Take her piece Mom, an audiovisual lament about longing to be reunited with her family and mother. Echoes from the final movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 31, Op. 110 drift through sparse sonic landscapes of soft cluster chords and breath-like sweeps of sound. In the distance, bells shimmer. On screen, we see images of a fetus bathed in red half-light. Writhing umbilical cords tether a child’s body to a protective maternal form. Fragments of Leonardo da Vinci’s Madonna Litta, Mary nursing the infant Christ, are interwoven.

Though intensely personal, Shariatzadeh’s artistic language transcends the realm of the private. You could say her imaginary spaces are also spaces of sublimation — where personal experience is transformed into universally felt affects (something other than emotion). She herself describes her works as becomings: “I hope my work offers a space where pain and grief can transform into strength, into hope, into beauty.”

Consider also Fabric of Sorrow (2023), dedicated to the victims of the protests that erupted in Iran a year earlier, following the death of Mahsa Amini. Shariatzadeh describes this work for ensemble and animation as “an imaginary architecture built from memories of the uprising. A building constructed from the flesh and blood of the women who gave their lives. At the heart of this structure, their grieving mothers weave a luminous fabric from strands of their hair.”

Her new piece Bluer Womb — a sanctuary in its own right — is closely connected to Fabric of Sorrow. Echoes of the Iranian uprising resound here too: ominous gongs and tolling bells, a searing cluster on the electric guitar described in the score as “a distant scream.” The animated images, projected onto a translucent screen in front of the musicians, include scenes from the Shahnameh, the Persian Book of Kings, in particular the tale of the mythical hero Rostam, who defeats the evil demon Div-e Sepid. Call it a mythic metaphor for the struggle against the current regime.

And yet, where Fabric of Sorrow was rooted directly in the uprising, Bluer Womb is a reflection — a contemplation of the emptiness and loss that followed. “So many sacrifices have been made,” says Shariatzadeh, “but the hoped-for revolution never came. That lost hope — that’s what this piece is about.”

At the same time, Bluer Womb carries a personal layer: the absence of a beloved sister who, for a long time, was like a mother figure to her. And so, in the animation, we see two sisters wandering through a crumbling city, seeking shelter in one another’s presence. In the womb of one, flowers begin to bloom — memories and future dreams of the beautiful place their city once was, and might become again.

Speaking of hopeful sanctuaries…

A Plea for Connection

In his short film The Chorus (1982), Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami (1940–2016) tells the story of an old man who can no longer bear the noise of the city. He switches off his hearing aid and withdraws from the world — but in doing so, he no longer hears his granddaughter ringing the doorbell. Outside, a chorus of schoolgirls calls him back in vain. With subtle simplicity, Kiarostami sketches a fable about silence and sound, old age and youth, isolation and connection. A poetic plea not to turn away from the world, but to keep listening to the voices that need to be heard.

Nadar Ensemble

Marieke Berendsen, violin // Nico Couck, e-guitar // Elena Evstratova, solo performer // Katrien Gaelens, flute // Yves Goemaere, percussion // Wannes Gonnissen, sound // Robin Goossens, business director // Pieter Matthynssens, cello, artistic director // Elisa Medinilla, piano // Thomas Moore, trombone // Stefan Prins, artistic director // Steven Reymer, video and light // Dries Tack, clarinet // Floor Vandevelde VGT // Veerle Vervoort, production manager // Video Editor Don’t Leave The Room and Silentium! (post-production & editorial input): Sasha Golikova

Joseph Brodsky

Translation by Alexandra Berlina

Don’t leave the room. This is better left undone.

You’ve got cheap smokes, so why should you need the sun?

Nothing makes sense outside, happiness least of all.

You may go to the loo but avoid the hall.

Don’t leave the room. Don’t think of calling a taxi.

Space consists of the hall and ends at the door; its axis

bends when the meter’s on. If your tootsie comes in – before

she starts blabbing undressing – throw her out of the door.

Don’t leave the room. Pretend a cold in the head.

What could be more exciting than wallpaper, chair and bed?

Why leave a room to which you will come back later,

unchanged at best, more probably mutilated?

Don’t leave the room. There might be a jazzy number

on the radio. Nude but for shoes and coat, dance a samba.

Cabbage smell in the hall fills every nook and cranny.

You wrote so many words; one more would be one too many.

Don’t ever leave the room. Let nobody but the room

know what you look like. Incognito ergo sum,

as substance informed its form when it felt despair.

Don’t leave the room! You know, it’s not France out there.

Don’t be an imbecile! Be what the others couldn’t be.

Don’t leave the room! Let furniture keep you company,

vanish, merge with the wall, barricade your iris

from the chronos, the eros, the cosmos, the virus.

Fyodor Ivanovich Tyutchev

Silentium!

translated by Vladimir Nabokov

Speak not, lie hidden, and conceal

the way you dream, the things you feel.

Deep in your spirit let them rise

akin to stars in crystal skies

that set before the night is blurred:

delight in them and speak no word.

How can a heart expression find?

How should another know your mind?

Will he discern what quickens you?

A thought once uttered is untrue.

Dimmed is the fountainhead when stirred:

drink at the source and speak no word.

Live in your inner self alone

within your soul a world has grown,

the magic of veiled thoughts that might

be blinded by the outer light,

drowned in the noise of day, unheard…

take in their song and speak no word.

“I want to say something, but I’m not allowed to”

Kevin Voets in conversation with Elena Evstratova, solo performer with Nadar Ensemble

The Theaterstudio at DE SINGEL was alive with artistic energy. A rehearsal had just been cut short: musicians tuned their instruments, a technician checked the cables, the projector flashed brief fragments of images onto the wall. In the middle of this restless scene, Helena Evstratova came over to join us at the table. She had spent the previous hours in the eye of the storm—as the solo performer in Don’t Leave the Room and Silentium!, two new works by Russian composer Alexander Khubeev—and then took a moment to sit down for a lively conversation, mediated by sign language interpreter Nine Van Belle.

Elena Evstratova (born 1976) was born in Siberia, studied in Moscow, and worked for almost twenty years as an actress in youth and regular theater. She specialized in mimicry, dance, and comedy, taught deaf children, and toured internationally. Since 2018, she has been living in Belgium, where she has collaborated with Silence Radio and Dahlia Pessemiers-Benamar, among others. At Nadar Ensemble, known for its musical experiments, she now faces an unprecedented challenge: translating Russian poetry into gestures, in dialogue with a contemporary music ensemble.

“Don’t leave the room. This is better left undone.”

This is Evstratova’s first collaboration with a music ensemble. “I am an actress, a dancer. I was familiar with rhythm, but music—that’s something else entirely. I can’t read music, and when I got the score, I didn’t understand a thing.”

Composer Alexander Khubeev developed a digital visual aid: bars that appear on a screen and show the duration of the notes. “That way I can see when something is short or long,” she says. “But still: it’s chaotic. Everything has to coincide exactly with the music, and I feel an enormous responsibility. I am the central performer—everyone is watching me. One mistake and the whole piece falls apart.”

Evstratova loves improvisation, but in this production that is impossible. “Everything is fixed. The musicians play strict scores. If I change anything, it no longer fits. It’s precision work: when the trombone plays a long note, I adjust my movement accordingly. My gestures must follow the music exactly.”

Don’t Leave your Room is based on Joseph Brodsky’s untitled poem from 1969, written during the Hong Kong Flu. It calls for isolation: ironic, melancholic, sometimes threatening. For Evstratova, it evokes memories of her childhood in the Soviet Union.

“I grew up with my mother in a tiny apartment; each family had only one room. The kitchen was communal, as was the hallway. I remember that when you had to go to the toilet, you had to do it as quickly as possible because there was always someone waiting behind you. You also had to be as quiet as possible in your room—the walls had ears. You were literally locked up between four walls. To me, Brodsky’s text feels like a prison—but also like protection. It says: stay inside, be silent, don’t speak. That’s censorship, but it’s also survival.”

At the end of Khubeev’s composition, her image is multiplied on the screen. The audience sees her talking to multiple versions of herself. “I don’t see those projections myself while playing,” she says, “but I understand the idea. They are pieces of myself that come out: my heart, my thoughts, my emotions. As if, after all, the inner voices that I am not allowed to express become visible.”

The last word of Brodsky’s poem is “virus.” “A virus is not just a disease. Negative thoughts also spread like a virus. That word can be interpreted in many ways. During Corona, everyone was locked up in rooms—just as Brodsky describes. I can relate to that. But it goes further: a virus can also be an idea that you can no longer stop.”

Silentium!

The second work, Silentium!, is based on Fyodor Tyutchev’s poem from 1868. It advises the reader to keep feelings and thoughts hidden, because once spoken, they lose their purity.

For Evstratova, this is recognizable. “When I read the poem, I feel that I want to say something but cannot – or am not allowed to. I can’t get it out. That is my experience as a deaf performer: there is always a gap between what I read, what I feel, and what I can express. The taboo, the censorship – that is in the language itself. That is why this poem touched me so deeply.”

Unlike Don’t Leave Your Room, Silentium! was created in close collaboration with her. “I first made a translation into Russian sign language myself. Not literally—that’s impossible. You have to choose emotions and images. I gave that version to Sasha [Khubeev] and he made music to go with it. Sometimes my gestures even inspired him to come up with musical ideas. My gesture for ‘feeling’ [pointing your index finger in your hand or towards your heart] reminded him of Morse code, like a heartbeat. That’s how the music and my gestures really came together. That’s why Silentium! feels a bit like my own child.”

How does a deaf performer experience poetry, in which sound and rhythm are so important? Does she have an “inner ear”? “No,” says Evstratova. “I don’t hear sounds, not even internally. But words do give me a feeling. I translate that feeling into gestures. The emotions are in my hands, in my body. For hearing people, poetry sounds; for me, it appears.”

But there is always a loss. “You can’t literally translate a poem into sign language. The rhythm and sound disappear. That feels like a form of censorship: there is always something I can’t say. But that’s exactly where the power lies. In that void, the emotion comes to the surface.”

Which of the two pieces is closest to her heart? “Silentium!,” she says without hesitation. “Because I was involved from the beginning. I was able to contribute my interpretation, and Alexander turned it into music. It’s my own work. Don’t Leave the Room was more difficult because I had to adapt to something that already existed.”

“Come and see with an open mind. Don’t expect to understand everything – neither the gestures, nor the music. It’s about the emotion that comes across. For hearing people, it may be strange to see gestures without sound. For deaf people, it’s strange to see music they can’t hear. But together it forms a new whole. I hope everyone feels what I’m trying to show.”

In Don’t Leave the Room and Silentium!, Elena Evstratova embodies not only two poems, but also a tradition of Russian poetry in a context of political oppression. Her body becomes an instrument that is silent and speaks at the same time. Where Brodsky ironically calls for seclusion, and Tyutchev seriously urges silence, she makes their words visible in a sign language that the audience cannot understand literally – but can feel all the more strongly.

The tension between incomprehension and emotion lies at the heart of this music theater project. Evstratova concludes: “There is always something I want to say, but I cannot—or am not allowed to. That is precisely where my art begins.”

Kevin Voets on behalf of DE SINGEL. Voets is head of research at the Royal Conservatoire of Antwerp and a lover of new music.

Elena Evstratova

Elena Evstratova (°1976) is a deaf actress raised and born in Siberia. Since 2018, she lives in Lochristi (Ghent). She obtained her master of arts degree from the Moscow Conservatory of Music. She also got her degree in General Arts with literature, costume and theatre history of Russia and Europe as main subjects. From 2000 to 2018, she worked as a professional actress in both youth theatre and regular theatre. Furthermore, as a deaf actress, she specialised in the theatre of facial expressions and gestures, dance and comedy. She also taught theatre classes to deaf children for years. During her professional acting period in Russia, she was often seen abroad. She toured Germany, Prague, Japan, USA, Turkey, Mongolia, Ukraine and across Russia. In Belgium, she joined the theatre company Silence Radio under the artistic direction of Dahlia Pessemiers-Benamar. Together they created the performance Portici (including Eurudike De Beul) and several dance performances.